Why Does this Plot Structure Inspire Revolutions (again and again)?

The Forbidden Romance of Beautiful Souls (part 1 of 2)

The future will show whether it might not have been best for the peace of the world if neither Rousseau nor I had ever existed.

- Napoleon Bonaparte

Great cities must have theatres; and corrupt people, Novels.

- Rousseau

If you’ve been following along with my adventures into the world’s most influential fiction, you’ll be glad to know, it’s the same book.

Again.

But this time it’s different. This is going to be a big one, because I think I might have found the granddaddy of them all. Understand this book, and suddenly Ayn Rand, and Lenin, and a whole lot more, all make a lot more sense.

This story started in Switzerland. It swept France, then Europe, then the world. It inspired a revolution. Across continents and centuries, people keep re-writing this book. Each time it inspires revolution.

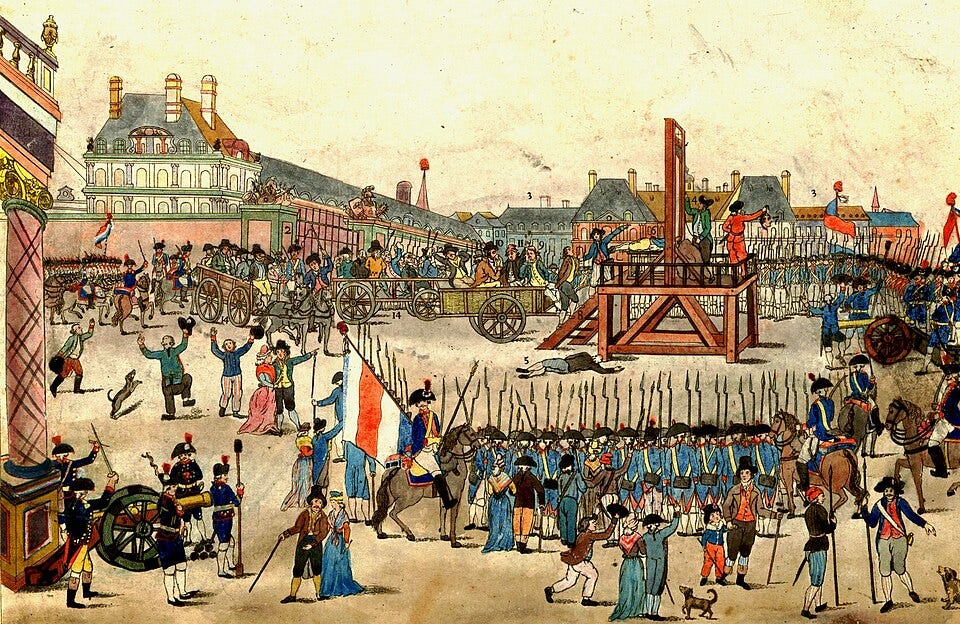

The French Revolution had one. The Russian Revolution had one. Chinese socialism appears to have had one. Tech-billionaires and neoliberalism had one. I suspect there are more. If you draw the boundaries loosely, to include entire genres and moods spawned from this origin, then major world events are repeatedly inspired by variations on this theme.

At the core is an archetypal plot structure and set of techniques, that when applied effectively by their very nature drive the audience towards social change. Fanatical revolutionary change.

We are going to unpack this plot structure. We are going to see why it works. We will be following in the path of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and his biggest success: Julie; or, The New Heloise, published in 1761.

The New Heloise was the mega-bestselling cult-hit oh-my-god-I-want-to-marry-the-author novel of the 18th Century. This novel was so popular you could rent it by the hour. Rousseau became the world’s first cult author pop-icon. The New Heloise was the novel of the French Revolution. People blamed the revolution on Rousseau. All the factions who mutually guillotined each other, all of them were Rousseau fan-boys. The New Heloise had huge cultural and literary influence. Literature as you know it was shaped by this novel. Rousseau is in your head. This novel was peak Rousseau mania.

And it’s all the same book. People keep rewriting this book.

The novel of the Russian Revolution, What Is To Be Done?, was a direct re-write of The New Heloise. All the talk of vice and virtue in Atlas Shrugged makes a lot more sense in the light of The New Heloise. Those are just the one’s I’ve read. There’s more. The New Heloise is itself built on the foundations of an Old Heloise - which is nearly 1000 years old, and among the most influential romance stories in history.

It’s Heloise’s all the way down! Let’s figure out why.

Warnings and Caveats

First, one big warning: this is something worth learning about, but not something to apply uncritically. Both the original and the adaptations include some seriously dangerous tendencies.

Virtue without Terror is impotent; Terror without virtue is bloody.

- Robespierre (the ultimate fan-boy, taking the fandom a little too far)

This story structure can easily fall into promoting narcissism and vicious us-vs-them purity wars. This is a story type which can and has created fanatics who executed their enemies in the name of “virtue”. Can a story do that? A mere piece of fiction? Apparently the answer is yes (or at least it gets people a long way in that direction).

However, I don’t think that nastiness is essential to the story here. With some awareness you should be able to avoid the narcissistic purity trap. What remains behind is both valuable and powerful. Indeed, this story cuts into something core to kind of era we are living in.

Second big warning: the fact that Atlas Shrugged is a book of the establishment should give you some pause. This is a story type which helped create the modern world as we know it. The story structure we’re looking at is a story that inherently drives towards revolution and individualism. It is a very “modern” story in the deepest sense of the word “modern”. Can you fix the world using the very tools which created it? Maybe? Maybe not? Either way, this is worth learning about, because it reveals something deep about how stories work and how social change happens. But it might not be the tool you ultimately want to use.

Third big warning: this stuff is complicated. I could be wrong. I’ve done my best to understand Rousseau’s writing, but there’s some limits. The first volume of the New Heloise is a properly structured tragedy. Apparently the other volumes (yes, multiple volumes) become somewhat meandering, and he starts endlessly ranting like Ayn Rand. I can’t say, because I couldn’t finish it for the same reasons as with Ayn Rand. I would lose my goddamn mind. I did read parts of one Mr Flick’s PhD thesis on this novel, because that was easier than multiple volumes of madness. Some of my comments will be coming from that (and similar) scholarship.

If you want to know what The New Heloise is like to read, imagine that Ayn Rand wrote a bunch of love letters in the style of Pride and Prejudice while tripping balls on ecstasy.

It’s wild.

Sometimes it happens that our eyes meet; involuntary sighs betray our feelings, tears steal from – O! my Eloisa! if this union of soul should be a divine impulse – if heaven should have destined – all the power on Earth – Ah, pardon me! ...

He never lets up.

My inability to finish either Atlas Shrugged or The New Heloise is not a coincidence – these are a specific type of book that repeatedly creates fanatics who try to take over the government.

It’s Heloises all the way down.

Comparative Heloise-ology

To give us our foundation, we’ll look at the original Heloise and Abelard alongside our three other Heloise-like books: The New Heloise, What Is To Be Done?, and Atlas Shrugged. This will show us the general structure of this story type.

This is just a general pattern, focused on The New Heloise and those works I have read. Many other works potentially belong to this lineage (Rousseau did inspire the entire Romantic movement after all). Key point: this is a broad family where each text was possibly inspired by one of the previous texts (directly or indirectly), reached for a similar mood, and inspired similar results. We will focus on The New Heloise as the origin and archetype. In practice you can deviate a long way from this, provided you maintain enough of the explosive core. Atlas Shrugged is a good example here. Others like it exist. Whenever I see a 1000 page book, filled with angsty heroes obsessed with vice and virtue, inspiring fanatical fans who want to burn down the entire world order - I get suspicious now.

That core plot structure truly is an explosion. It shows up first with the original Heloise and Abelard.

The Old Heloise

The romance of Heloise and Abelard is a true story that took place in Medieval Paris, circa 1100 AD. This is some serious archetypal romantic tragedy. Romantic literature has been influenced by this tale ever since. The story underwent something of a revival during Rousseau’s era, which is how he picked it up.

The quotes bellow will give you a feel for this romance. Rousseau is very much copying-pasting this stuff. Note the intensity of feeling, the talk of virtue and vice, the talk of shame and guilt and revenge, and the painful separation. This is all going to be a big deal for Rousseau. This is all core to the explosive nature of the Heloise story.

But I am no longer ashamed that my passion had no bounds for you, for I have done more than all this. I have hated myself that I might love you; I came hither to ruin myself in a perpetual imprisonment that I might make you live quietly and at ease. Nothing but virtue, joined to a love perfectly disengaged from the senses, could have produced such effects. Vice never inspires anything like this, it is too much enslaved to the body. When we love pleasures we love the living and not the dead. We leave off burning with desire for those who can no longer burn for us. This was my cruel Uncle's notion; he measured my virtue by the frailty of my sex, and thought it was the man and not the person I loved. But he has been guilty to no purpose. I love you more than ever; and so revenge myself on him. I will still love you with all the tenderness of my soul till the last moment of my life.

And now for his reply...

I had wished to find in philosophy and religion a remedy for my disgrace; I searched out an asylum to secure me from love. I was come to the sad experiment of making vows to harden my heart. But what have I gained by this? If my passion has been put under a restraint my thoughts yet run free. I promise myself that I will forget you, and yet cannot think of it without loving you. My love is not at all lessened by those reflections I make in order to free myself. The silence I am surrounded by makes me more sensible to its impressions, and while I am unemployed with any other things, this makes itself the business of my whole vacation. Till after a multitude of useless endeavours I begin to persuade myself that it is a superfluous trouble to strive to free myself; and that it is sufficient wisdom to conceal from all but you how confused and weak I am.

I remove to a distance from your person with an intention of avoiding you as an enemy; and yet I incessantly seek for you in my mind; I recall your image in my memory, and in different disquietudes I betray and contradict myself. I hate you! I love you!

- Abelard, letter to Heloise

Okay! What happened with these two? Here’s the quick summary.

Abelard, he’s a big deal genius philosopher/poet/theologian. He’s in Paris, being cool and poetic. Young Heloise comes along. She is also a genius poet girl. They have their meet-cute. Abelard becomes her tutor. Their lessons mostly involve hot sex. She gets pregnant. They’re living with Heloise’s uncle at the time. The uncle is not happy about this. Heloise gives birth. They call the kid Astrolabe (because they’re hipsters). They have a secret marriage. The uncle turns violent. Abelard gets attacked and castrated (ouch!). It all ends in tears. Heloise and Abelard both enter monasteries. They can never meet again. But they still love each other, and it’s all very sad. As you can see in Heloise’s letter, a question is hanging over the whole affair – are we at fault, or is the world?

This is the forbidden romance of beautiful souls. Can you feel the explosion buried within that question? This story is the most revolutionary story in the world. That question is the revolutionary question.

The Central Problem

Heloise and Abelard is a tragedy of forbidden romance between beautiful souls. This sets up a narrative problem. We want them to be together, but society is stopping the usual romantic arc from happening. That leaves three possible endings:

Give up on love. This is impossible, because it’s true love.

Give up on society. This is impossible, because they are beautiful souls and can’t suffer disgrace or do harm to others.

Change society. That’s a revolution.

This romantic tragedy circles around the injustice of the core dilemma – abandon love or abandon society. The subtext is an argument for social change (more or less overtly stated).

How does each of our stories handle this?

Heloise and Abelard:

They embrace love, then suffer the consequences. They forsake both love and society, by taking religious vows. This was a socially acceptable exit from regular society at the time. Abelard seems to see the whole thing as a mistake. Heloise maybe hasn’t given up. One attempted way out of the dilemma is to transcend both love and society with spirituality. But the story remains a tragedy. The push towards revolution remains latent within. The spirituality itself can start to take on a certain radicalism (Abelard would later get in trouble with the Church).

However, the Medieval world seems to have been able to absorb or deflect that revolutionary energy. The energy within mostly funneled into the courtly love tradition (the kind of story that Don Quixote satirizes). It would take until the modern era for Rousseau to unlock the explosion latent within.

Write no more to me, Heloise, write no more to me; ’tis time to end communications which make our penances of nought avail.

- Abelard’s final letter, choosing religion over love.

The New Heloise:

Rousseau adapts the original. The lovers embrace their love, but it can never be. She is a noble, he is a commoner, and the father is prejudiced against violating his family’s aristocratic standing (Rousseau’s story is scandalous by the standards of times). In volume one Eloisa ultimately faces a choice between being with her lover and disgracing her family, or separating from her lover to be with her family. All options are bad. It’s a tragedy. Rousseau also reaches for spirituality.

What Is To Be Done?:

Chernyshevsky tries to turn Rousseau’s tragedy into a comedy using the power of rational egoism and socialism. He lives after the French Revolution, where events themselves have shown option three is viable.

Atlas Shrugged:

Ayn Rand turns the comedy into an apocalypse using the power of rational egoism and capitalism. She lives after the Russian Revolution which has shown the socialism to be a catastrophe. Forbidden romance is demoted to a subplot, making this the most different in terms of plot. However, the core driver is still “Beautiful souls vs the world”. The dilemma is the same. She chooses to give up on society, in order to destroy society, so the world can be remade in the image of liberated individual beautiful souls.

The Revolutionary Core

Hopefully you can see why this is an inherently revolutionary story. The ending of volume one of The New Heloise, will leave you shaking your fists, screaming “That’s not fair!” The plot is set up so you will blame the tragedy on the very concept of aristocracy. The fans of this novel beheaded a lot of aristocrats.

Chernyshevsky didn’t really need to explicitly put a revolution in there. Even if the author sticks with a tragic ending, or tries to transcend it with religion, the readers will be so upset that they themselves will reach for the revolutionary answer – which is exactly what happened with Rousseau. This drive can still happen even if the author did not intend that message. Rousseau was not a political revolutionary.

This is what “the personal is political” means as a plot structure. The stronger the drive being denied, the stronger the desire to overthrow that barrier. What stronger drive is there than true love between beautiful souls? The barrier is the social order. The romance drives the reader to demand the overthrow of society. That is the central power of the Heloise-like story.

The Source of Regeneration

Okay, so you want to overthrow society. What do you do? Where does regeneration come from? That is the big question, then and now.

If everything you’ve ever been taught is flawed, how do you know what is right? If your world is corrupt, how do you know what a good world would be? From what grounds do you criticize or offer alternatives? How do you distinguish vice and virtue, good and bad?

Historically we get few major options. You’ll notice people using these today.

Return to the past. People didn’t have these problems before. We’ve lost something. Let’s go back.

Look to other cultures. Those people seem to be doing better than us. Let’s copy them.

Use reason and evidence. Analyze the causes of our woes. Design future systems. Implement the new improved system.

Look within. Fall back upon yourself. What makes you feel good or bad? What do you desire or hate?

Look to the Universe. Find something bigger than humanity. That might be nature, God, mysticism, or similar. You will find the answer in the great beyond.

Most Enlightenment thinkers were focused on reason and evidence. Rousseau was the weird guy for that time. He is very much pushing for introspection and transcendent ideas about Nature and spirituality. That is the task of The New Heloise.

The novel exists to push you towards a regeneration via inwards experience. He is rescuing the individual from society, and leading them towards their moral regeneration. Both Ayn Rand and Chernyshevsky are doing the same thing (they try to combine reason and feeling into “rational egoism”).

We’ll stick with Rousseau here, because he’s the origin of this stuff. The following quote is the first major “Author Message” style passage after the Novel’s introduction. Here the tutor/Lover Boy, is outlining his approach to education. He’s just told his student/Lover Girl that he’s throwing out all the textbooks and math. Screw that nonsense! He has a radical education in mind:

If we would but consult our own feelings, we should easily distinguish virtue and beauty: we do not want to be taught either of these: but examples of extreme virtue and superlative beauty are less common, and these are therefore more difficult to be understood. Our vanity leads us to mistake our weakness for that of nature, and to think those qualities chimerical which we do not perceive within ourselves; idleness and vice rest upon pretend impossibility, and men of little genius conclude that things which are uncommon have no existence. These errors we must endeavour to eradicate, and, by using ourselves to contemplate grand objects, destroy the notion of their impossibility: thus by degrees our emulation is roused by example, our taste refines, and everything indifferent becomes intolerable.

Got it?

If you want to know what’s good, look inside. You’ll feel it. You can’t learn goodness in a textbook using algebra. But we have a problem. What if I’ve never experienced extreme goodness? I live in a corrupt society. Would I even recognize virtue? I am at risk of saying, “Nah, that can never happen!” simply because it has never happened to me. This is an error to be eradicated, and you do that by looking at examples of extreme goodness.

And what is this book?

Exactly. Rousseau achieves his objective within the confines of the book itself. By reading the book you will be exposed to the superlative example of virtue. That example will itself transform you. These are characters you can emulate. This could be you. All these Heloise-like books work via moral exemplars. You can become the characters. Literally.

And it works.

When it comes to laying out entire life patterns, ways of being, behavior, thought, feeling, virtue, ... you can’t teach this with facts. But you can do it with examples. If your aim is cultural regeneration, and your focus is on the individual, then you need to give them examples. This is the one form of regeneration that hits most powerfully at a personal level. The ideal vehicle for an inwards form of regeneration is art.

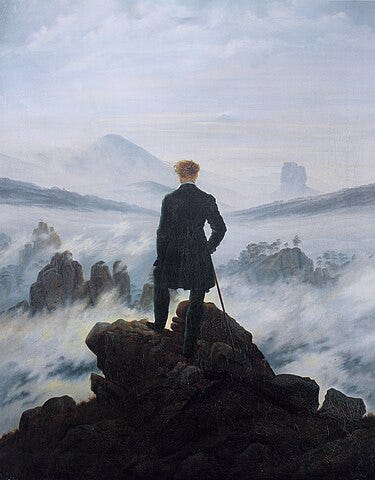

To lift your reader to a new way of life, you need to show them a beautiful soul. The greatest plot for a beautiful soul is the Heloise romantic tragedy. That plot will drive them to overthrow society in the name of a new way of being.

Authenticity

What does a regenerated individual look like?

We’re talking about the kind of person who has cast off everything in society that is fake, artificial, and harmful. They haven chosen true virtue over the false virtues and vices of the world. When you do this, what you’re supposed to be left with is the sincere and authentic self. As a consequence all these exemplary characters are very intense, sincere, and earnest people. They know who they are, but they live in a world that doesn’t get it.

That’s the theory.

We live on the other side of this cultural moment, so we face the new problem that our ideas about authenticity (derived from these books) have themselves become inauthentic and toxic. Authenticity easily degenerates into mere narcissism. Inner-truth easily degenerates into elevating gut-vibes above evidence. That said, a call to authenticity remains a valid source of regeneration. This is call to distinguish between external opinion, and your internal reality.

What do you actually feel? Why? What do you truly believe? Why? Are you just acting? Is that who you really are?

The forbidden romance plot crashes into these questions. Our lovers are forced to be fake so their love remains secret. They feel the pain. They rage against the inauthentic. The gulf between the inner truth and social opinion is thrown into high contrast. The tension between the two becomes unbearable. You want to tear down the walls.

The Strong Female Lead and the Ideal Male Lover

All these romances were written in strongly Christian patriarchal societies. Even Ayn Rand is still up against 1950’s opinions. The others are in a world of arranged marriages. In that context we get a story were the woman is equal to the man. They have sex outside marriage. We don’t judge them for it.

The maxims I imbibed as a child were so severe, that love, however pure, seemed highly criminal.

– Eloisa

All of our stories here are doing this. The lead character is the woman. Ultimately she comes off as better than him.

A romance plot by its very nature demands the lovers be worthy of each other (otherwise it’s exploitation or creepy). Now, if it’s a romance between poetic genius beautiful souls, that means that woman is going to be fairly empowered. The quality of the man also matters. He is a beautiful soul too. We open up space for an exploration of what an ideal man even looks like. He’s a poet, not a thug. He’s the kind of guy who gets horny for an empowered woman. Set in a patriarchal society, this kind of romance becomes inherently radical. Again, we are driven towards removing artificial barriers and prejudices.

Didactic and Erotic

We have a romance between poetic geniuses. This means you can get horny and philosophical at the same time. That combination unpicks one of the biggest downfalls of political writing – the goddamn preaching.

When you have a romance between philosopher geniuses (especially if it’s a tutor-student situation), they will naturally talk about big ideas. It’s who they are. It’s plot relevant. Done well it all holds together as a coherent story. Rousseau does this fairly well (in volume one anyway). The others, less so. Ayn Rand is the worst. Even badly done, this stands in stark contrast to those awful the manifesto “novels” that just lecture you.

At its best this erotic-didactic combination really does work. The sensuality intermingles with the philosophy. They share energy. The philosophy becomes more personally meaningful. The sensuality becomes elevated in its meaning. We are striving to live what we believe at the deepest levels of our being. This is a lived philosophy. This goes beyond mere academics. This is personal transformation. And so goddamn sexy too.

At the climax of volume one, Rousseau can spend several pages dismantling the arguments for aristocracy, and it doesn’t feel like a lecture. The argument is plot relevant. The entire romance hinges on the outcome. The entire plot has built up prior emotional and logical support for that argument. You want that character to win the argument. You want love to win. If we can just defeat aristocracy then our lovers can be together! Come on! Win! That is how you “preach” without preaching.

None of these authors can resist actual preaching. Even Rousseau breaks, and then lectures people for 500 pages. But they do show it can be done.

Frustration, Martyrdom, Hedonistic Asceticism, and Sadomasochism

Look, this is a weird one, but it keeps happening. They all have the BDSM kink. Ayn Rand is the most obvious. Rousseau straight up tells us in his autobiography that he liked a bit of slapping. The New Heloise wallows in sexual frustration. Even Chernyshevsky had a weird relationship to his wife.

This can’t be an accident. It’s a not a bug, it’s a feature. I’m not sure why. Here’s some speculation.

This story type hinges around a sense of victimhood, persecution, frustration, even martyrdom. A forbidden romance is 100% sexual frustration. If you consider the psychological build up to a revolution, a lot of people are experiencing frustration and suffering. Sadomasochism elevates suffering into a kind of explosive pleasure. That pent up energy can then be released in a violent martyrdom or by guillotining aristocrats.

Maybe? I don’t know. BDSM is the kink most interested in power, for what it’s worth. They all have it.

Soap Opera

If you wanted to class all these books into a genre, they would be Soap Operas. Are they technically Soap Operas? Well... no. These books are madness. But they’re closer to Soap Opera than anything else. These are not, say, all detective novels or courtroom dramas. Soap Opera is the revolutionary genre.

The New Heloise is a foundational novel in the genre of “Sentimental novels”. The closest modern descendant is the Soap Opera. What Is To Be Done? is a romantic comedy of manners. Atlas Shrugged is a bit more grandiose, but even there much of it is about family dramas, sex, relationships, the usual Soap Opera fare. Even the original Heloise and Abelard story has Soap Opera moments. The whole story is a sex scandal... with love triangles involving the maid... and wild moments of family betrayal and reciprocal testicle removal.

Why Soap Opera?

We don’t normally think of Soap Operas as being torch bearers of revolution. But they obviously can be. The personal is political. It’s about values. Changing a society’s values is a revolutionary act.

If you put heroic characters into a grand setting, like a Star Wars space opera, then the focus will be on their physical courage, the adventures, and so on. You seldom get a deep examination of ideology or values, except in the most simplistic Good vs Evil terms. If you put those same heroes into the tiny domestic setting of a Soap Opera, the entire struggle turns introspective.

His voice was made harsh by the oxygen respirator. “Luke, I am your father,” said old man DV spooning fried eggs onto Luke’s dinner plate.

Luke stood up. “Bullshit you are. You wait till now to tell me?” He pushed the plate aside. “I’m sick of fighting with you old man.”

“You know it’s true.” DV reached out his hand, still clothed in a black oven mitt. “Come on. Talk to me, kid.”

“No way man.” Luke gripped the wall, like he was about to tumble down into an abyss. “If you were my Dad, then you had your chance and you blew it. You chose the dark side. Is that what this is? Redemption? Screw you!” He stumbled out of the room like he’d been stabbed with a light-saber.

“Luke, come back!” called the old man, wheezing through the tube. “She’s your sister!”

Soap Opera’s worlds of gossip and scandal are a deep examination of values. You create some domestic scandalous event, and then you do the gossipy nitpicking. Who is right? Who is wrong? Why did they do it? What would you do? Did Eloisa choose the right option? Is he bad for her? Is he a good man? Is the father a bastard? Should we abolish the aristocracy in the name of love? That’s what Rousseau, Chernyshevsky, and Ayn Rand are all doing with their teen romance and melodrama. The personal is political. It’s about values you can apply in real life.

Also, Soap Operas are just fun. How else would you convince someone to read 1000 pages of angst-ridden introspective insanity where nothing happens? Seriously. Nobody ever does anything in these books.

Intensity

The New Heloise might be the most melodramatic book I have ever read. Wow. Just wow.

All of these stories make use of high emotional intensity. What Is To Be Done? is the most subdued, but even he has full on melodrama and dream sequences with Goddesses. Ayn Rand is basically having orgasms over metal smelting.

Why do this?

These books are generating emotional energy within their readers, then directing that energy at their philosophical targets. Rousseau spends an entire novel building up extreme sexual tension, and then at the climax denies you. “Aristocracy won’t let you do that, bro. Sorry.” By that point you have generated enough emotional intensity that you can’t just let it go. Noooooo! Love must prevail! Nooooo!

That is the energy required if you want to do more than win mere agreement. That is the energy required for personal transformation, an inwards regeneration… followed by building a guillotine and overthrowing the government.

The sublimist wisdom is attained by the same vigour of mind which gives rise to the violent passions; and philosophy must be attained by as fervent a zeal as that we feel for a mistress.

- Lord B, friend to the tragic lovers

These are also all deeply religious stories. This is intensity of feeling and intensity of thought and subject matter. The original Heloise and Abelard are theologians in monasteries. Ayn Rand and Chernyshevsky are both using religious imagery. Rousseau is coming up with his own mystical romantic nature spirituality.

All of them are cutting deep to the core. What really matters in life? These are books you read to figure out the meaning of life. If you want people to dedicate their lives to a cause, that’s the level required.

Length

Dostoevsky makes fun of Chernyshevsky for not knowing when to shut up. Ayn Rand is attempting to write an infinite novel. Rousseau writes a single novel across multiple volumes. They all do it. They hook you with some mystery and romance. They hold on as long as they can.

I suspect this is largely truth by repetition. They are putting forward new values which are likely to be rejected by the reader the first time. So they keep doing it. We look at every angle. Every argument. Again, again, again. Rousseau and Ayn Rand can introduce you to their entire body of thought, in fictional form, because they give themselves the space.

The aim is to transform the reader, and that takes time and effort. They do know how to write. They are deliberately pushing for maximum length regardless of the artistic cost.

Metafiction

We saw this a lot in What Is To Be Done? Chernyshevsky took this technique from the New Heloise, and ran with it to the point of insanity. Rousseau is much more restrained. He uses a prologue and footnotes (yes, footnotes in a novel – it works?). Ayn Rand is the least insane here. She does include character commentary on art and literature within the story. All of them need to use some amount of meta-fiction for the same reason.

If you do something that truly breaks free of your culture, you are going to look really strange.

You have to address that somehow. The biggest enemy is always “the sophisticated reader”, because they carry the most literary preconceptions. Our authors here overcome this threat by appealing to populism and “true values”. They get you on their side, against the literary snobs. All of them do this.

Rousseau gives us a very clear example. The prologue recounts a dialogue with his publisher (or at least he has that vibe). He runs through the arguments pre-emptively, and turns it from a criticism into a hook. Yes. This is a bad book. Bad, baby, bad. Those snobs in Paris, they won’t get it.

But you might.

If you’re a beautiful soul.

He then turns this into an offensive against the Paris snobs. I’m just writing a regular book for regular people. Maybe these letters are all true? Maybe? I don’t know. I’m not trying to get famous or nothing. I’m just trying to help the regular folks. This is real life. Real people. How it really is. You can’t stop me publishing. I’m doing this thing, even if you don’t get it. Snob.

How’s that for a meta-fictional hook? While doing this he outlines his theory of how fiction works. Some of his readers decided this book was true, or even autobiography.

If your readers like what you’re doing, you can get them on your side against the critics. You set up a world of virtue and vice, us and them, and then you suck your reader inside.

The Mind-Invasion of Alien Words

Novels are “Double-voiced”. When I write a character, it is both the character and myself speaking. Therefore every statement in a novel has the capacity to carry a double meaning. That can be subtle, or overt (which is when readers find you preachy).

Double-voiced language is important when we hit ideologically charged words: virtue, crime, honour, etc. The characters are able to speak these words as typically fits their society. At the same time the author can give those words new meanings. The characters appear to be having a normal conversation, but actually the reader is being invaded by new meanings.

All three of our authors are likely doing this. It can take a bit of cultural background to figure out the key words. All of them seem to care about virtue. Again it’s about values. Virtue and vice. Good and bad. Those are the foundations of any system of values.

Rousseau takes a word like “virtue” and subtly redefines it. Our lovers start out trying to maintain virtue – a very chastity based virtue. They have sex anyway. They are still committed to virtue – which has by now become something new. Likewise, double-voicing means he can put republican arguments in the mouth of an English aristocrat, and get away with it (he even hangs a lampshade on it with a metafictional footnote).

Imagine taking some of the key words from our contemporary culture: hardworking, efficiency, freedom, patriot. Bring to mind the usual definitions. Now imagine redefining them. A hardworking man who is unemployed. An efficient operation which never does bookkeeping. Imagine having a billionaire CEO give a passionate speech praising hardworking unemployed homeless people. That’s what Rousseau is doing.

It sounds mad. But it works.

Changing a society’s values necessarily involves going through this kind of terminology. Reorganizing, redefining, discarding, inventing. New values need to be communicated in words people already understand. If the reader absorbs this newly redefined language then it becomes impossible for them to speak or think in a way that supports the existing system. They are literally speaking a new language.

The core values underneath have shifted. We spend a lot of time going, “Is that real virtue, or just fake virtue? Is that real honour, or just fake honour?”

Youth

All of these stories involve fairly young people. Teens, early twenties. Ayn Rand has mature adults, but she includes many flashbacks. The energy is youthful, juvenile, teen angst. These are books that work well for young people. They seem to hit people when they are young. About thirty years later you’ve had a generation come of age under the influence of these novels. That’s when you get the revolution.

The New Heloise was in 1761. The French Revolution was in 1789. That’s a 28 year gap. Robespierre was 31 years old.

What Is To Be Done? was in 1863. Lenin wrote his manifesto of the same name in 1901. That’s s 38 year gap. Lenin was 31 years old.

Atlas Shrugged was in 1957. The neoliberal turn started around the 1980s. That’s a 20 to 30 year gap. It’s a little messier because this appeals to people already in power. But it’s similar timescales.

Beyond mere chronology, these are coming of age novels. However, “growing up” is a negative process of corruption and compromise. The world is corrupt. Youthful innocence remains authentic. Youth is a hammer used to smash a corrupt world.

The core conflict in these stories tends to be within the family, and to be inter-generational. The youth have the new ideas. The old people have the old ideas. The old is blocking the new. This reflects the actual social reality in a society undergoing rapid change. We can see this happening in our own time, for example with the youth protests for climate change.

Revolutionary change seems to rely on a certain amount of youthful idealism. Cynics don’t start revolutions (and it’s an open question what mature adults might choose to do).

Virtue and Vice

The core problem of the Heloise-like story is beautiful souls vs. society. The question that hangs over it is who is right and wrong? The beautiful souls or society?

In order to answer that question we need a thorough investigation of good and bad. Right and wrong. Virtue and vice.

To be a beautiful soul implies you are already in some way good. These are by definition moral exemplars. The scales are tipped in their favor. A romance plot drives hard to unite the lovers. The scales are tipped against society. But to be a satisfying story, we really need to explore. What makes someone a beautiful soul? Is that enough to justify ignoring society? Who is right? Who is wrong?

The question of vice and virtue is the central obsession of these stories. Rousseau fans became obsessed with virtue. They guillotined people in the name of virtue. What Is To Be Done? was explicitly outlining a “new person” shown in stark contrast to the corrupt world of fools and swindlers. His fans sought to become new people creating a new world. Atlas Shrugged draws a harsh division between the “makers” (virtue) and the “looters” (vice). Her fans have sought to create a world of liberated virtue (genius entrepreneurs), while destroying vice (social welfare). John Galt’s epic speech is all about vice and virtue. It’s all the same basic impulse.

Utopia and the Community of Virtue

Lastly, all three novels include some exploration of the ideal society. Ayn Rand has Galt’s Gulch. Chernyshevsky has his workers sowing cooperative, and dream tours of a future Crystal Palace. Rousseau gives us a well managed virtuous homestead in Switzerland (he’s the original off-the-grid lifestyle farmer).

These utopias are both a call to pre-figuration, and a tease. These utopias are things that can be done in the real world, to a limited extent. But they never truly satisfy the core dilemma of the plot. The only way to do that is to make the utopia universal. That means revolution.

In parallel with the utopianism, we see the formation of friendship groups and communities. Our lovers are not alone. Other people come forward who “get it”. You are left with the feeling that within the world is scattered a secret society of Good People. You can join them.

That’s the feeling these books leave you with. Go out and find other fans of the novel. Find the Good People. And what are you virtuous fan-boys all going to do? You are going to create the utopia, obviously. You are going to have a revolution.

Conclusion

We could get more into Rousseau specifically, because he does do some things unique to him. However, the above gives the core features. We’ve gone on long enough. I am planning to follow this up with a more practical guide. I know this was a lot.

This is the Atomic Bomb of literature. The tragedy of forbidden romance between beautiful souls might just be the most volatile story you can write, if you live in a volatile society. Think about your own “forbidden romance”. What do you desperately want that society wont let you have? Make it personal, and you’ll understand what Rousseau is doing. If you can hit that core just right, then you should be able to feel the energy pulsating in your hands. You should be able to understand, emotionally, why the French Revolution happened.

At the core of a revolutionary moment is this emotional experience: I cannot live my life in this society unless it changes! This is unbearable! This is wrong!

The Heloise-like story hits that energy. The potential result is an explosion.

The romance of beautiful souls puts forward an ideal type of person, shows them in contrast to a corrupt world, and urges you to destroy the corruption in order to liberate those beautiful souls into the bliss of true happiness. It fills this story with intense emotional, even religious, energy and holds you in that state as long as possible. You are drawn to identify yourself as a beautiful soul, to see your own struggles as being against a corrupt world, and to push yourself towards the only satisfactory answer – a revolution.

And that is how a romance story has been a key driver in multiple revolutions.

Playing with explosives requires a certain amount of wisdom and self-awareness. Rousseau blew himself up. If you try to direct that energy, you need a good understanding of what you are promoting. If you leave that energy undirected, it will attach to anything it can find – and you might not like what it finds. When you pit old and new values against each other, some people will take it further – into a virtuous purity war. Be aware of that. All these books, and their authors, feel deeply neurotic and unhealthy to me. As we ourselves strive for something healthier and wiser, we might drift a long way from this tragedy of vice and virtue.

And yet, there is a truth at the core. This story appeals for a reason. We just want to live, to love, to be free. But this world is messed up, and wrong, and standing in our way. We want to tear down those walls, and embrace our love.