This is part of a series on writing climate change for fiction

Today we’re looking at people in groups. Unless you’re telling a tale about a child raised by wolves on a desert island, then you’re going to be dabbling in the realms of social psychology. Relationships. Culture. Crowds. Likewise, spend five minutes thinking about climate change and you’ll realize it’s very hard to solve this stuff at the level of individuals.

Social psychology is an enormous subject. Merely touching on some highlights could get fairly involved. This stuff also gets fairly abstract. Therefore, to pin this all down in a way that makes sense for storytelling we’re going to follow the epic tale of Bob and Emma...

It’s Friday night. When Bob gets home from working at the construction site, he finds his daughter Emma waiting for him on the steps. He gets out of his SUV, holding a bag of sausages for tonight’s BBQ. He notices Emma has dyed her hair blue. Kids these days. “What’s the matter baby girl?” he asks.

A look of contempt flashes across Emma’s face. “Dad!” she says, “I’m not a baby! I am sixteen! Today I joined Friday’s for Future! Guess what? You’ve ruined my future! You don’t even care! All you care about is money! And... and... sausages!”

And so begins their journey!

IDENTITY

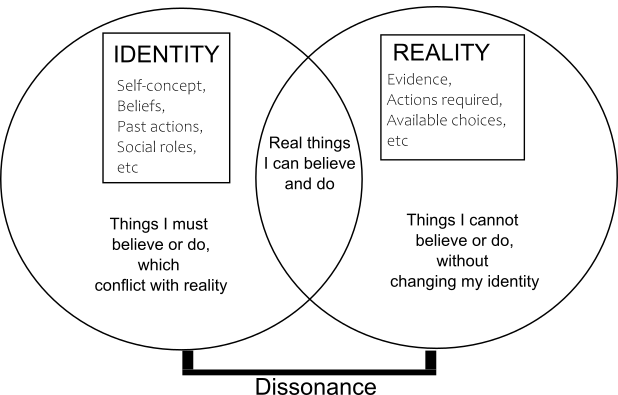

The first big social force we need to consider is people’s sense of self. Identity includes a large number of factors (memory, skills, gender, ethnicity, profession, ...), and is somewhat nebulous (go ask a Buddhist, “What is Self?”). Identity is a mix of hard facts and social expectations. Identity is both deeply personal, and also shared with large groups. For our purposes, the important thing is that identity constrains and directs behaviour.

Identity is something we take for granted. We can forget how important identity is, or get frustrated at inane “identity politics”. Remember – a stable positive identity is a essential human need.

Unstable identity occurs in serious mental health issues. Lacking identity means you get pulled every which way depending on circumstances. Trying to live out multiple conflicting identities quickly becomes a mess. Similarly, having a negative sense of identity (e.g. “I am worthless”) leads to collapse and self-destruction. Life becomes chaotic and implodes. Lacking a sense of your social role is also toxic. People feel alienated, adrift.

A stable positive identity makes our lives coherent – both to ourselves and to others. That coherence forms the foundation for effective action. That coherence allows us to function as stable members of a coherent society.

The flip side of that stability is rigidity.

Identity can come into conflict with reality. Especially in times of rapid change. The actions required for effective climate action are pushing a lot of people into a position of identity conflict. The only way out is to either change yourself, or deny reality. Therefore we get one of the main sources of climate denial – a backlash against reality in order to maintain a stable sense of self.

Bob fires up the BBQ. The propane ignites with a roar. Flickering red flame. The hiss of gas. He just got a new BBQ, spent a bomb on it, burns through fuel like crazy, but cooks like a dream. His friends gather around, each with a beer in hand, and compliment “The Beast”. It’s the biggest, shiniest BBQ they’ve ever seen.

Bob feels a sense of pride. This is who he is. He throws the best BBQs. This is his thing. Everyone knows it. This is how he connects with his buddies. Friday night at Bob’s is an institution. This is the one night a week when his wife doesn’t cook, and Daddy brings home the bacon – literally.

Emma gives her father the side-eyes. “How much gas does that thing burn?”

“Ah...” Bob freezes up. He wants to say that it’s huge, burns like a F-16 jet fighter, welcome to The Beast! He wants to impress the boys. But now... he doesn’t know what to say...

We often assume people are driven primarily by self-interest. However, identity can override self-interest. People will engage in wildly irrational behaviour to maintain their sense of self. If you lack a self, there is no self for self-interest to apply to. Identity is an essential human need.

Previously we looked at how people can engage in counter-productive emotional management to avoid difficult feelings. One big reason for that is the fear and powerlessness climate change makes people feel. The other big reason is identity threat.

All sorts of strangeness can spill out from this. Simply avoiding stuff because you feel overwhelmed is a self-limiting problem – people disengage. Identity threat gets far weirder.

When you see seriously strange versions of climate denial, consider if there’s identity threat in there somewhere. This is one of the motivators of conspiracy theory thinking. Identity protection seems to generate a much more active rejection of reality. Indeed, there can be a certain hostility, even disgust, to the possibility something is wrong. This is a threat. A violation. Like a disease, or a punch in the face. You’re really hitting people we’re it hurts.

An obvious example of identity threat is the hysteria around transgender people. Trans people mess up the traditional gender identities – people go ballistic as a result. Hence we get hysteria about hidden rapists in women’s bathrooms.

Climate change causes similar issues, they’re just more subtle. Masculinity is tied to projecting power, and therefore to fossil fuel use. Patriotism gets screwed up when your country’s wealth is based on fossil fuels. People’s career-identity is based on particular industries and technologies ( I am an oil man/dairy farmer/automotive maker etc). Political parties are built on having core identities linked to the identities of their voters – all of which then constrain what actions they can and can’t do.

On and on it goes.

...Bob laughs. “Did you hear?” he says to his friends. “My daughter’s become a hippy! You’re gonna have to go home guys.” He drops sausages onto the grill. He stops. Bob despises the beardie-weirdie green scene – that just aint me - but he also thinks of himself as a good father. Humiliating his daughter is not exactly fatherly. He smiles in appeasement at Emma. “The world isn’t going to end just because of one BBQ. Will you forgive us?”

Emma glares at him.

He shuffles awkwardly. “We always have a BBQ,” he says, feeling annoyed.

His mate Jeff speaks up. “You know, they exaggerate that climate stuff. It’s the corporations. Follow the money.”

Bob’s not sure what Jeff is on about, but it sparks a thought. “Yeah,” he says, “I guess, what I’m saying is... you’ve got to form your own opinions in life. People get up in arms about all sorts of stuff these days. Nothing wrong. Just keep your head screwed on.” He smiles at his daughter. She’s a kid. He’s the adult. She needs that voice of stability. Bob turns up the grill. He makes a mental note to buy a new gas bottle.

Social Cleavages and Identity

Previously we touched on how climate change becomes a political football when it gets caught up in broader social conflicts. Rich vs poor. Religious vs secular. Whatever it might be.

Identity is central. You identify with your side. They’re your people. How could you possibly believe what the other side believes? This is where identity makes the leap from being personal, to being overtly political.

Jeff comes up alongside Emma. “Who got you into that protest then? One of your teachers? They’ll hire anyone nowadays.”

Emma tenses. “A whole bunch of us went. Nobody made us.”

“You heard about it online though, didn’t you?” He looks her in the eye. She makes the faintest suggestion of a nod. Jeff shakes his head. They always target the kids. He’ll have to warn Bob, before this gets out of hand. Bob’s a good guy, but he just doesn’t understand the world like Jeff does.

Cultural Trauma

Identities belong to more than one person. We identify with groups. Previously we’ve looked at how trauma effects individuals. Trauma can cause both breakdown and growth. Much of this happens because trauma can break a person’s sense of self.

This process can be scaled up to entire societies. Genocides, dictatorships, civil wars, natural disasters, pandemics. Such things leave collective scars.

Climate change has the potential to:

Cause cultural trauma in the future

Cause cultural trauma now

Be worsened by our pre-existing cultural traumas

Cultural trauma is fundamentally about identity and storytelling. An individual trauma overwhelms your ability to cope, and breaks your sense of self. A cultural trauma does much the same thing, just at a societal scale. People’s sense of collective identity gets damaged.

For example, many Americans seem to have been undergoing a cultural trauma. They came out of the Cold War believing they were the Good Guys™. That was their collective American identity. And then they’ve watched as their country slides into the dark. That vibrant positive identity has broken. Who are we? Why did this happen? Is it Russia’s fault? The banks? The Mexicans? The woke mind virus? The fascists? Who? Why?

Cultural trauma is a collective experience. This leads to certain quirks. And I mean, this can get seriously bizarre. The trauma exists in the social imagination, not in anyone’s actual lives.

You can have a “trauma” without anyone being alive who actually experienced the traumatic event. Events like the Holocaust are kept alive in cultural memory, with very few people being direct survivors. That memory exists in books, museums, pilgrimages, family stories. This makes cultural trauma very different than individual trauma, which exists in your own mind alone.

In theory, a culture can both invent and forget traumas. Indeed, this is an active battlefield for people aiming to shape the narrative of who we are. Jewish people work very hard to sustain that Holocaust memory. Meanwhile certain other people deny the Holocaust ever happened.

We can argue about who is closer to reality, but that’s beside the point. True or not, cultural traumas form a narrative for understanding any suffering present in our collective predicament. The world is bad because...? We need to protect ourselves from...? You feel vulnerable, lost, and angry because...?

Central is the construction of who “we” are. If you reject this framing of “we”, then the whole thing falls apart. If I am not part of this “we”, then this trauma you’re claiming has nothing to do with me.

This brings us to climate change.

If, how, and when climate change becomes constructed as a cultural trauma will profoundly shape how global society responds. It will decide who “we” are, and therefore who “we” choose to help.

Catastrophic climate change has not yet happened (although, watch this space). Because it is possible to invent a cultural trauma, we can experience a trauma before the event has even happened. Therefore we are living in anticipation of catastrophe. Those imagined futures can become present cultural traumas ("Look at those bastards who ruined my hypothetical future!”). The point is how it shapes our sense of meaning right now.

Likewise we can also forget and ignore. Terrible events may be happening, but if they are never pulled into a coherent collective narrative then our collective sense of meaning never changes. We will be living in denial. We will persist in an increasingly delusional sense of collective identity, in the desperate hope that the thing we’re ignoring will just go away.

This then is the fight over the climate narrative.

One side is attempting to pull a future apocalypse into the present. The other side is trying to push present harms out into the irrelevant margins. This is a battle over storytelling.

For suffering to become a collective experience a social process must happen. A shared narrative needs to emerge about why we are all suffering. As with individual trauma, the response to the event is a product of society itself, not just the event. Trauma is something we do, not merely something that happens to us. Storytelling is central. Any narrative of cultural trauma will answer certain questions:

What happened?

Who is to blame?

Who was harmed?

Does that victim represent us as a collective? Were “we” harmed, or just “them”?

I see at least two big possibilities here.

Climate change becomes a globally unifying narrative. “We” becomes all living things. All peoples. All species. All are suffering from the same cause. We are all in this together.

Alternatively climate change becomes globally fragmenting. You hurt us. They are to blame. We must fight them. No universal narrative ever emerges. Denial and accusation pervades. We get scapegoating. People are left to suffer alone, or retreat into tribalism.

These are roughly the two big narratives that emerged for the Covid pandemic, a similarly global event. “We’re all in this together” vs “The China virus”.

Emma passed the news article over to her father. “This is what I’m saying Dad!” The news showed a flood, all of Pakistan underwater.

Bob looked at the news, and the words passed over him. That was somewhere else, someone else, not here, not my problem. He didn’t understand what she meant.

Emma looked at the news. She felt the pain in her heart. This is my world. This is us. This is what we have become.

Crisis of Meaning & Hollow Souls

People lacking a sense of identity will find a substitute. This applies strongly to fascist movements, but it also drags people into every substitute imaginable – from cults, to drug addiction, to climate activism.

Nazism has nothing to do with race and nationality. It appeals to a certain type of mind.

.... It is the disease of the so-called “lost generation.”

.... Those who haven’t anything in them to tell them what they like and what they don’t—whether it is breeding, or happiness, or wisdom, or a code, however old-fashioned or however modern, go Nazi.

A lack of a core self is destructive to the human spirit. A healthy sense of self is grounded in something. An unhealthy sense of self is buffeted by external forces, unable to direct its own actions.

The erosion of a sense of self creates the kind of person Dostoyevsky was satirizing in Notes From the Underground. Unstable, self-loathing, contemptuous, power hungry, prone to escaping into fantasy. Those fantasies can include political fantasies. They might take actions to make those fantasies into realities. They might want to get elected and become a dictator. They might decide to write utopian political fiction. They might dream that they can save the planet from the apocalypse. The details don’t much matter – the aim is to fill the vacant hole in their heart.

Now, because identity is collective, this erosion can happen en masse. You might get a society, a demographic, or an era where this becomes troublingly common. If, by some chance, you just happen to live in such an era, things might get fairly wild. You might find yourself seeing a lot of Nazis, cults, drug addicts, and yes, also climate activists.

Emma feels herself both drawn to and repulsed by the man. He’s one of the organizers, and he radiates a peculiar nervous energy, a mad intensity buried underneath a polite sobriety. “It’s a matter of life and death,” he says calmly, leaning in towards Emma, before getting sidetracked onto how no one but him is willing to do what it takes. But he will. Yes. He will.

SOCIAL NORMS

After identity, the next big social force is norms. The rules. The expectations. What everyone else is doing.

We have two types of norms:

1) Injunctive – what you are supposed to be doing.

2) Descriptive – what everyone actually appears to be doing.

For example: Let’s say you have some trash to throw away. “No littering” is a injunctive norm. You must dispose of that trash correctly. Seeing litter dropped everywhere is a descriptive norm. Actually no one cares. Therefore in this situation you’ll feels some tension. You’re not supposed to litter, but everyone else is, so actually it’s okay to litter. Maybe?

Norms apply to most areas of life. We’ll go through that soon. Norms get enforced in many ways too. e.g. ridicule, bullying, instruction, motivational posters, clichés, role models, etc. Which norms you are exposed to depends very much on where you are and who you know. Some norms are very obvious (e.g. do not murder is literally in the Law). Most often norms are very subtle. You’re expected to know, without being explicitly told.

The point is, we are all regulating each other’s behaviour. Just like with identity, this is a necessary part of social life. The alternative is chaos. The question is: what norms are we going to have? Some of our current social norms might not work well in a world of climate change.

People are both explicitly and implicitly fighting over norms all the time. Norms are a direct target for anyone trying to change the world.

Behaviour Norms

The most obvious type of norm is regulating actions. What are you supposed to do? What are other’s doing?

For climate change this is a bit of a mess. Some injunctive norms are telling us to change, while others are telling us to remain the same. Most descriptive norms are telling us to remain the same. The status quo is, by definition, the thing everyone is doing now. However, some people are changing – so there’s a lot of tension.

The number of climate relevant norms is too vast to count. Some noteworthy areas are norms around masculinity, work, wealth, and purpose – anything that intersects with political or economic issues.

Bob has a difficult week with Emma.

He’d hoped it was just a phase, but she hasn’t let up. On Wednesday she told him a long story about how so-and-so’s father really listened to her, and he did such-and-such. That’s what a good father looks like. Bob can’t remember the details, but Emma’s point was clear. You’re a dinosaur Bob. Feeling that pain he promised her they’d do cooking inside this Friday, on the electric oven.

However, that Friday, Bob had a conversation with their elderly neighbour. The old guy had seen Bob’s new BBQ and decided to get one of his own. “You’ve got to enjoy life while you can,” said the old man, giving Bob a wink.

That evening Bob fires up the BBQ without even remembering he’d ever planned otherwise. What’s the point, if we’re miserable, he thinks.

Emotion Norms

What are you supposed to feel about climate change?

Emotions are social. Emotions have rules. Emotion norms dictate what is a socially acceptable range, intensity, duration, display, and target of your emotions. This is what you ought to feel, and how you ought to look while feeling that way.

Emma yells at her father. “But you said!”

Her mother turns and snaps. “Emma! Cut that out. That’s no way to talk to your father.”

A scowl frozen on her face, Emma stops, biting her lip and holding her silence.

How we actually feel, and how we are supposed to feel can differ markedly. To bridge that gap, we need to engage in emotional work. Think of the retail worker smiling and saying, “Have a nice day!” several thousand times to people they hate. We all do this.

We can do surface acting, where we just fake it. “Have a nice day! (You prick).” We can also do deep acting, where we fake it until we make it. “Have a nice day sir! Who am I to judge why you tried to grab my ass? We all have bad days, right?”

Either way two things happen.

First, the social structures that these emotion norms enforce are kept in place. If unhappy retail workers expressed how they truly felt, it would be called “Going on Strike”. Second, huge amounts of repression and cognitive dissonance can build up under the surface, if the mismatch between the real feelings and the norms is big enough. That may, or may not, explode one day.

Which brings us to climate change. We’ve got some fairly big emotions to work with there.

A comprehensive list of climate emotions:

Amazement, surprise, disappointment, confusion. Isolation, shock, trauma. Fear, worry, anxiety, powerlessness, dread. Sadness, grief, yearning, solastalgia. Overwhelming anxiety, depression, despair. Guilt, shame, inadequacy, regret. Betrayal, disillusionment, disgust. Anger, rage, frustration. Hostility, contempt, discontent, aversion. Envy, jealousy, admiration. Motivation, urge to act, determination. Pleasure, joy, pride. Hope, optimism, empowerment. Belonging, togetherness, connection. Love, empathy, caring, compassion.

These feelings can be extremely widespread, and for some people very intense. All of these emotions are subject to emotion norms. How often do these emotions actually get expressed? In what form? Would you even feel comfortable admitting to some of these emotions in public?

If one of these emotions violates the norms, then it will be suppressed. The true weight of that feeling will never be felt internally, nor expressed socially. Therefore the entire subject is robbed of its true emotional weight. That is the point of emotion norms – they stop destabilizing emotions running rampant across society. Again, norms are necessary. The questions is, what norms are you going to have?

Now imagine what happens if people fully express what they’re feeling, in public. Because that has implications. Emotions drive behaviour. Emotions demand a response.

“No, I won’t shut up!” says Emma. “I won’t shut up just because you feel uncomfortable. I’m scared, and you’re doing nothing. I’m angry, and you don’t seem to care.”

Her parents looked at her, their mouths open. “But, of course we care,” said Bob.

“Then what are you going to do?”

Conversation Norms

What is acceptable to say? When? Where?

If you can never talk about an issue, then it is impossible to do anything about that issue as a group. Everyone is left to deal with the issue in isolation. It is very difficult to know, feel, or act on an issue personally if society at large refuses to do so. It is possible to get caught in a collective suppression of reality where knowledge, feelings, and actions do not connect and are not acknowledged as fully real. The elephant in the room is ignored.

Everyone may actually care. The problem might be that they lack a forum in which to speak.

Every venue has conversation norms regulating what is appropriate to talk about in that context. You don’t discuss genocide at a wedding. You don’t confess to adultery during game night. You don’t give radical political speeches at the office Christmas party.

Climate change, as a subject, falls outside many of our conversation norms. It involves politics, strong emotions, scientific technicalities, and other stuff which just doesn’t fit well in most venues. When exactly are you supposed to talk about this?

If you violate a conversation norm, people will rapidly steer the conversation back inside the norms.

... Bob sighs. “Emma, can we... how many sausages do you want?”

“I’m a vegetarian now,” she replies.

“Okay.” Bob turns away, and looks at Jeff. They both roll their eyes.

“Did you see the game?” asks Jeff.

With relief Bob lets the conversation drift away from Emma’s teenage meltdown. “Now that was a match!” he says.

Attention Norms

The universe contains an infinite number of things you could pay attention to. You need to filter that. Attention norms dictate how you should do that filtering. What are you supposed to notice? What is important enough to care about?

We can see the same thing, and yet see different worlds.

Emma’s biology class stands overlooking the valley. The teacher reads the landscape for her students. See those reeds? That means the soil is wet. See those exposed sediments on that cliff? We can read five million years of history there. See that fish? See that insect? See that bird? These are things you are supposed to notice.

On the other side of the valley, Bob stands with the property developer and a consultant for the new construction project. The consultant reads the landscape for his client. See that farmland? That’s been rezoned for housing subdivisions. See those trees? They protected, you can’t clear them. See these mortgage rates? See these interest rates? See this risk profile? These are things you are supposed to notice.

Every profession and subculture has attention norms. Society in general also has attention norms. The society around us can direct which thoughts we are capable of having by directing our attention. That attention decides who counts as “us”, “now”, and “here”. Attention decides what the past was, and what the future can be. Attention decides what exists, and what does not.

Again, norms are necessary. Democracies all have a norm that elections matter. If we weren’t all paying attention then elections wouldn’t work. The question is, what norms are you going to have?

Climate change took a long time to make into the mainstream attention norms. Now that climate has established itself as “A Thing That Exists That You Should Think About”, the new norms are focusing us on specific angles and framings of the issue. Just spend five minutes on the internet, and you’ll see how we might have some problems here.

Bob opens up the internet browser, and types in: climate change. The search results inform him of just what his daughter has got so upset about.

Google News tells him about a lack of snow for ski fields in the USA.... and a lack of snow for ski fields in Switzerland... and financial losses for African farmers. As far as he knows Emma has never been skiing. They do not live in the USA, or Switzerland, or Africa. Why does this matter to her?

A link takes him to Reddit. So he searches there too. He finds endless forums hurling abuse at each other. F@&% you liberals! F@&% you climate activists! F@&% you climate deniers! Another set of forums are gripped by panic or claims of conspiracy. Are we doomed? We’re doomed! No, it is exaggerated! It’s all a lie! As far as Bob can tell climate change is sheer hysteria and political nonsense. Emma clearly needs adult guidance.

He clicks over to Youtube.

The search results give him a bunch of explainer videos. Heat intercepts with the gas and the blanket and like a greenhouse and this is bad because Africa and skiing. He clicks away. So what? Leave it to the scientists then? He scrolls through more hysteria, until finally the recommendations divert him away, and he finds himself watching a video about Trump.

Every act of communication shapes our attention norms. Art is arguably one of the most deliberate attempts to shape attention. Stop. Listen to this sound. Look at that colour. Focus on that behaviour.

When it comes to your own work, what are you leading people to give their attention to?

SOCIAL STRUCTURE & COORDINATION

People are not arranged randomly. Particular patterns govern who knows who. The shape of these patterns determines many things. What information do you see? What seems normal to you? What social norms are you exposed to? Groups can have beliefs, emotions, and intentions that exist as a group. The whole is more than the sum of the parts.

Action as an individual is fairly simple. I want to do something. I get up. I do it. Action as a group gets much more complicated. We can get ourselves into some strange situations simply due to group dynamics. There’s many different perspectives for looking at this, so we’ll consider a few.

Class and Identity

Radical politics has traditionally viewed society in terms of class. This can bleed over into climate politics, because climate politics is an extension of much older political struggles. Class is your position in a socio-economic hierarchy. Working class, middle class, upper class. The idea is that people tend to stick within their own class, and conform to class-based subcultures.

This is true to some extent. It depends when and where you live. This was very much true in times when social classes where defined by law and custom. However, modern society doesn’t always fit classes that well. Economic conditions are rapidly changing. People are very mobile, and very individualistic. Real people just don’t fit the categories very well.

One response is to define new classes (e.g. the bourgeoisie and the proletariat gives way to the “precariat” and the “professional managerial class”). Another response is to focus on identity categories (e.g. gender, ethnicity, etc). All of this is true enough, it’s just a bit crude. The idea of Kyriarchy can add some nuance here. People experience the effects of one identity category through the other identities they hold. A man, and black. A woman, and wealthy.

However you conceptualize this, class and identity groupings is one lens for viewing how people relate to climate change.

Bob has always considered himself a blue-collar working man. He enjoys beer, BBQs, and sports. He votes conservative. He prides himself on personal responsibility and giving people a fair go. People like him just don’t go in for that hippy-dippy latté drinking save the whales stuff.

In contrast, Bob’s wife Pam considers the whole family to be middle class. She’d quite like to buy both of them lattés, and save the whales, she just can’t afford to. They’re renting, and financially strained. Even so, she really has always thought of themselves as middle class. After Emma’s big tirade, Pam started buying eco-brand dish soap. The package has an image of a woman hugging a blue-eyed blonde-haired little girl. Pam’s half-Asian. But it still feels right for her.

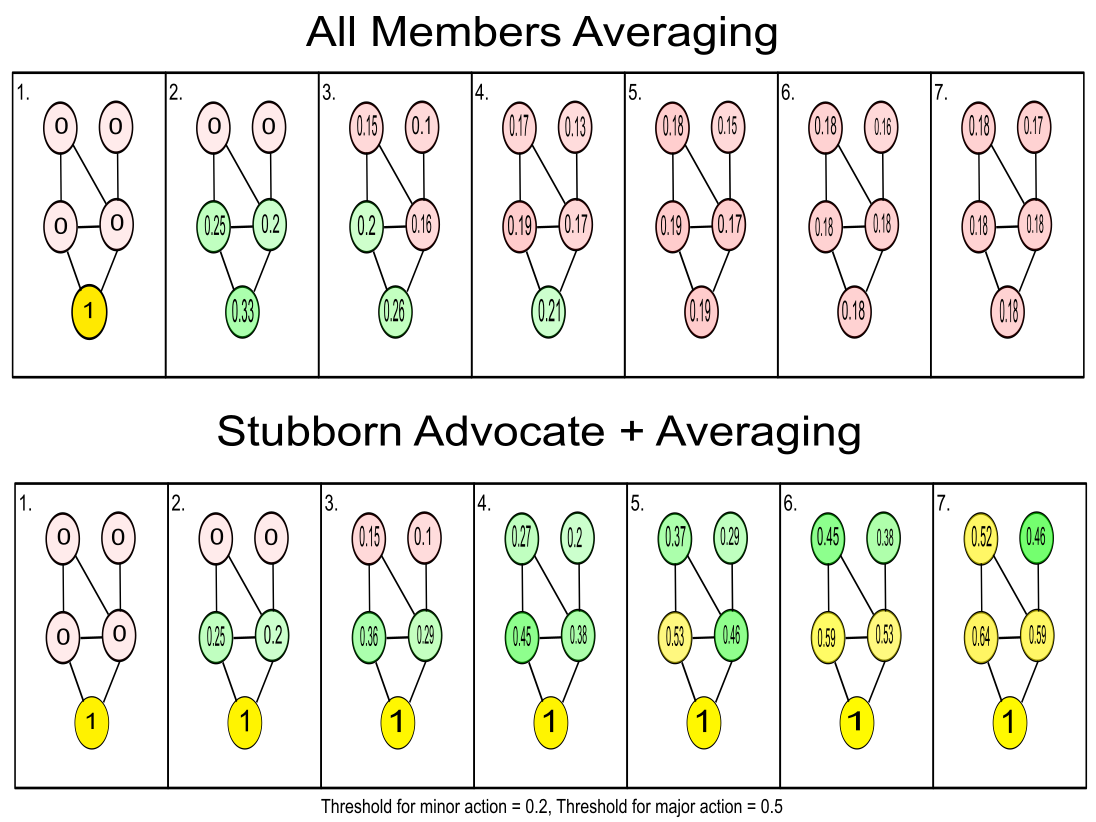

Social Networks

A more realistic, but much more abstract, way of viewing social structure is networks. This is an entire field of research, and impossible to summarize. The key point is this: everyone exists in a web of connections. That entire web has properties, not just the individuals within.

A lot of factors can be relevant. How tightly connected are people? How much clustering is there? How many loose distant connections exist? Depending on the answers, that entire structure may behave differently. This is all very abstract, but it’s a useful model to have in the back of your mind.

A concrete example would be political polarization. If people start sorting themselves based on political beliefs you’ll end up with two mostly disconnected networks. Ideas and behaviours in one network will fail to make the jump to the other network. You’ll end up with two parallel versions of society, indeed even parallel versions of reality.

Bob just didn’t know anyone like that. What did he and greenie tofu boys have in common? He didn’t know. Such people existed purely in his imagination. He’d never met one. Where would he find one? Likewise he imagined they saw him as some boneheaded chest-thumping caveman. Maybe if they came to a BBQ they’d see he wasn’t so bad.

Emma, for her part, did consider her father a caveman, an opinion formed on the basis of experience and teenage spite. Her horizons were rapidly expanding. One of her school friends knew a guy, who knew a guy, who was the organizer of the protest. Following that chain of links she’d found herself in a new world. Everything her father cared about was to these people irrelevant. They were so different she could scarcely believe that they’d had always been here, living in the same town as her family.

Homophily & Acrophily

How do we decide how to arrange ourselves? Why isn’t it random? Two big forces shape how we make that choice.

Homophily is the tendency of people to associate with those similar to themselves. Some of this is choice. Some of this is accident of birth and geography. Given a choice people prefer homophily. Similar people find it easier to interact. They share identities and social norms, therefore have fewer conflicts. It’s easier.

This tendency to “stick to our crowd” has implications. Radical socialist activists tend not to hang out with religious conservatives and vice versa. Therefore you get two isolated groups with wildly different opinions about subjects like climate change. On the flip side, that similarity makes it easier for people to organize within their group. This all gets rather messy – it depends on the context.

Okay, so now you’re in a socially homogenous group. How do you figure out all those social norms? What does your group believe? What does “normal” look like?

Acrophily is the tendency to be drawn towards those who are more extreme than we are. Most real people are messy, contradictory, a mix of identities and views. Extreme people distil things into their purest form. This clarity gives them a certain appeal. You can say, “Yeah, that’s what I believe!” In reality, you probably don’t exactly believe that, because you’re a mess. But they’ve distilled something you think you should believe.

Acrophily can lead to an illusion. We think society is far more polarized than it really is. Everyone is actually a mess. This is the true descriptive norm, if only we could see it. Being a mess is normal. But, each group is paying attention to the most extreme versions of their belief. And those extremes very much are polarized.

Hence we end up with climate activists who think the world will end in 15 minutes, and climate deniers who claim the Illumanti is behind it all. Meanwhile we’re all in the middle going, “So... I guess I’m with those guys?”

The more conflict Bob has with his daughter, the more he finds himself turning to his friend Jeff. He can be an abrasive guy, but you can never say he’s confused. Jeff lends him a dog-eared book that will, “sort him out.” Bob flicks through the pages. Obama and the New World Order. Green prophets of doom. Follow the money. Bob doesn’t know what to think, but Jeff does seem to be fairly knowledgeable. Meanwhile, Emma is learning about the Rojavan revolution from a guy with dreadlocks on Youtube.

The Abilene Paradox, Silent Majorities, and Propaganda

Nobody cares. Nobody wants to act on climate change. Nobody wants the world to change. This is just self-evident. Right?

Right?

When I act alone, as an individual, I know my own opinion. I have 100% access. When I act in a group, I only have access to the opinions that others express. So, how does a group know what the majority opinion actually is?

Communication is never 100%. Some people are silent. Others are bullying. It’s a mess.

This mess can result in illusions. We all want to choose option A. However, we all think the group wants option B. Therefore we end up choosing option B. This is a failure of communication. This “Abilene Paradox” happens all the time for small groups.

For climate change we can scale this up. Then we can add in people who are intentionally trying to create or destroy illusions. Society has a general shared impression of how willing we all are to take climate action. Depends on who you are, but there’s definitely a vibe. That impression shapes how motivated people become to take actual actions.

For example, people regularly claim ownership of the “silent majority” against any social movement they dislike. Does such a silent majority exist? Who knows! The point is to shape people’s view of the group opinion, and therefore shape what the group opinion actually becomes. Likewise, an attempt can also be made to create an impression of a very loud majority. Is it real? Who cares! People will shape their own behaviour based on what they think society at large believes. Therefore manipulating that impression is paramount.

Bob pauses while reading Jeff’s climate book. The page has a list of scientists saying climate change isn’t real. There is no consensus. This whole thing has been foisted on us by the Elites. He suddenly feels a lot less guilty about the new BBQ.

Meanwhile, Emma is listening to a visiting guest from an overseas climate protest group. The man speaks passionately. “Afraid of sounding alarmist, millions stay silent. So the majority and its power are hidden. It’s time for the climate majority to make its voice heard!” says the guest. Emma sits up straight. Yes. The world agrees with me. I am the majority. I refuse to be silent.

CONCLUSION

Social psychology is a huge subject, and we could go on forever. What we’ve covered should be enough to give you a basic feel.

Remember – climate change is ultimately a social problem. Climate change exists at the scale of global society. Therefore social psychology will necessarily be the dominant lens for understanding what is going on with people’s behaviour. However, climate psychology often gets framed in terms of individual psychology only – that’s a tendency you’ll need to actively resist if you want to understand the world.

People have social identities which empower and constrain their actions. People shape themselves to follow social norms. People exist in relationship to other people, existing as groups which take actions as groups. Everyone who is successfully changing the world knows this, and is trying to leverage this.

Next time we’ll be looking at the psychology of power.

Return to menu.