This is part of a series on writing climate change for fiction.

This is a problem we keep banging into with climate change – it’s big. Very big. The social, political, and economic forces to blame exist at planetary scale. The individual hero of a Hollywood movie is too small. Photos from outer-space leave out too much detail. Capturing both the scale and the detail is too overwhelming. We are contemplating the forces which created us and everything we know.

How are we supposed to understand this mess?

Today our task is to understand the fight for the climate at a planetary scale. The truth is, climate change must be understood at large scale, or not at all.

THINKING AT PLANET SIZE

The world is a big place. Where do we even begin? To understand a global event, we need the ability to think globally. This is a skill to be learned.

Okay, quick side note: like everything with this subject, the language gets problematic. I am going to use the word “global”, just be aware this word is vexed. Planetary. World. Gaia. Pick a different word if you prefer. The point is, we’re talking big. Everything you’ve ever known big.

To truly understand everything is impossible. Instead we need to apply some conceptual tools. These tools simplify everything, and allow us to be specific. Where should we focus attention? What questions should we ask? How do the specifics fit into their global context. A single protest or oil company advert doesn’t mean much in isolation. Our aim is to learn to see the whole world, even while sitting in one place. These particular tools here are just a few perspectives among many. They have limits. But we do have to use something. The human mind is incapable of grasping everything.

These are the questions to ask. Think of this as connections, size, and process. What connects to what? How big is it? What is it doing?

Connections – Thinking in Networks

In everyday life we treat places as independent. When I go to bed, I just go to my bed. I am in my room. It’s just my room. Here. Now.

When I am in bed, I am not also in a factory in Pakistan, nor a pine forest in 1975, nor the Shaolin temple in the 16th Century. I am here. Not there. I am in my bed.

But if I consider all the ways the items in my room are connected to the wider world and to history, then I actually am deeply tied to all that and more. The old bed frame is made from pine. A pillow has a “made in Pakistan” label. A book on Tai Chi sits on the bedside table. When I am in bed, I am also in the world.

By thinking in terms of connections, relationships, networks, we can break free of the narrowness of one place/one time. Think of all the possible connections that exist in a given place: supply chains, language and cultural groups, family relationships, institutions, rain clouds, migratory animals...

The world is deeply interconnected.

While everything is connected, some things are more connected than others. If I were to look at a bedroom in Sweden or Uganda, then the connections would be very different than appear in my own bedroom. Those places are different not just because of where they are on the map, but due to the differing web of connections within which they sit. We each sit at a different point in the global web.

If you want to take network thinking a step further you can think in terms of mutual influence, and co-creation. Even inert objects can shape the world around them. As a simple experiment, rearrange the furniture in your room. Take something major, like a desk, and remove it. See how your own behaviour now changes in that space. You put the furniture there, but the furniture was also putting you places. All things in the web exist in a dance of mutual influence and co-creation. Now expand this insight to a global web of people, plants, animals, information, buildings, and more. That is the world. All of it is exerting mutual influence upon the whole. You’ll never understand the totality, and yet you can catch glimpses of those ever-weaving threads.

The fight for the climate lacks clearly defined sides. If anything the struggle is marked by it’s fluidity, self-contradiction, and alliances of the absurd. At one moment the Pope and Neo-pagan witches are in agreement. At another moment an electric vehicle tycoon is helping fossil fuel interests gut the government. At yet another moment fossil fuel companies were funding climate research. Big environmental issues such as climate change break the organizing logic of the modern world. What emerges instead is the underlying reality that was always there - connections. What does exist are clusters of networks, all pushing the world in various directions. Who is allied with who, and who is pushing what is all very fluid and ambiguous.

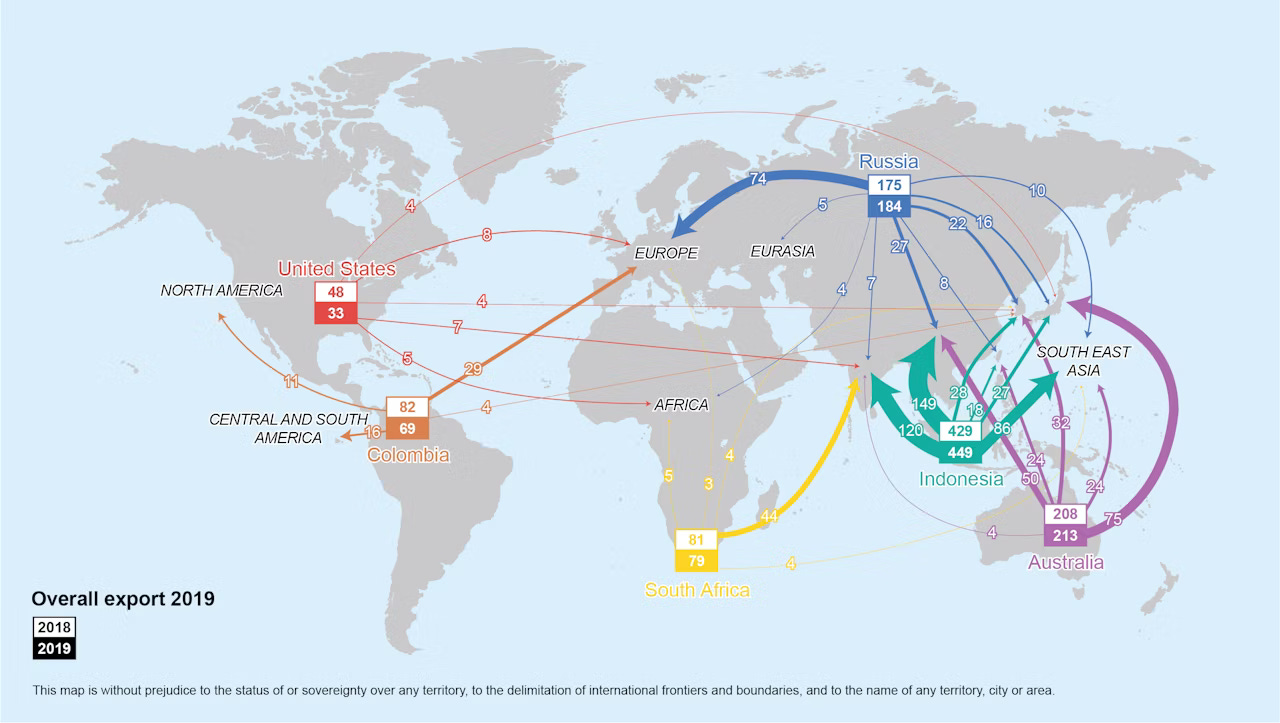

For climate change some big networks to consider include:

Social ties for movements (both activist and obstructionist). How do people know each other? How do they get involved?

Networks of political power (e.g. alliances between states, international ties between political parties, etc). Who can exert power over who? Who can coordinate with who? Who can oppose who?

Supply chains (e.g. fossil fuels, car manufacturing, etc). Where do the materials come from? Who is manufacturing them? Who is transporting them? Who is using them?

Finance. Who owns what? Where is the money invested? Who controls the levers of interest rates, currency values, prices? Who pays?

Networks of information and culture. Where do people get their news from? Their values? Beliefs? Who do they talk to? Who believes them?

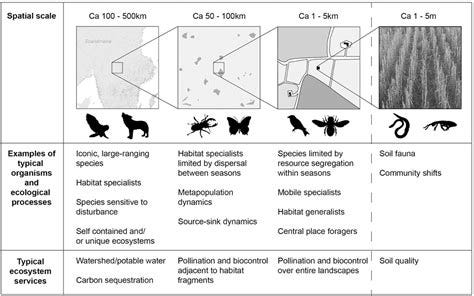

Size – Thinking at Different Scales

“Think global, act local.” That’s the answer right? The problems are global, whereas you are local. Do what you can where you are. Makes sense. Right?

Scaling says, “No.”

Think it through a moment. What counts as local? What is global? If I’m on the internet, am I local or global? If a local business uses global supply chains, is it a local business or a global business? If I burn fossil fuels in my backyard, releasing CO2 into the global atmosphere, am I doing that locally or globally?

A proper understanding of scale is the way out of this mess. First we need to throw out both “local” and “global” as concepts. Instead, you need to consider the process you are interested in. That process takes place at a certain scale.

Global warming takes place at the scale of the planet (the atmosphere doesn’t care where emissions happen). National elections take place at the scale of nations (mostly). The thoughts in my head take place in a blurred zone between me as an individual, the city I live in, English as an historical cultural block, and the global internet. I am neither “local” nor “global” in any simplistic sense. The mortgage on your house is the global financial system is many mortgages on many houses. Local is global is local. Some processes occur firmly at a specific scale. Other process can exist across scales.

Failing to understand scale leads to serious confusions.

If you define one scale as being “The Correct Scale”, then you’ll get stuck. Individual solutions don’t work in isolation, and neither do municipal, national, regional, or global solutions. All scales need to be considered together (depending on the process).

With climate change we’ve tended to get stuck at three scales: the individual, the nation state, and the United Nations version of global. None of these scales work well in isolation. The “solutions” they produce tend to get wrecked by something happening at a different scale. The UN reaches an agreement, which gets complicated by a national election, which gets complicated by geopolitics, which gets complicated by the psychology of individual dictators or billionaires – all happening at different scales. The natural scale where real power operates is fluid. Our institutions tend to be statically fixed at one scale. Many decisions are being made in a condition of functional anarchy because no institution actually exists at the scale of the process in question.

Forget “Think global, act local.” Instead think and act at the scale that matches the process in question. That’s a lot harder to do, and makes for a terrible slogan. Different aspects of climate change cover a wide spread of scales, from the individual to the planetary. Emissions are truly global. Some impacts can be hyper-local. The politics is a chaos of everything in between.

Process - Core and Periphery

The world does far more than just sit there. The world is alive. The world has a metabolism. Certain things must happen for the global order to remain alive. That metabolism structures the world. Certain process must happen in certain places and not in others.

The characteristics of a location will depend strongly on where that location fits within this global metabolism. Wall Street is a very different place than a Bangladeshi garment factory, and yet both of these places are part of the same system. They would not exist as they are without each other. These are not locations, so much as processes and relationships that get embodied at specific locations. The same process can move locations. Those factories started out in China, then shifted to Bangladesh. The process keeps moving and evolving, transforming the substrate of the world which it is metabolizing.

The Core-Periphery model gives us a way of framing this process (look up Immanuel Wallerstein for more). In this model, we have three types of place.

Core: high wages, high technology, many types of products made. A Wall Street banker lives in the core.

Periphery: low wages, low technology, few types of products made. A Bangladeshi factory worker is in the periphery.

Semi-periphery: a mix of both.

The periphery provides cheap labour and raw materials. The core produces profits, and consumer goods. Keeping these processes spatially separated stabilizes a system which depends on keeping some people disempowered (can you imagine what might happen if those impoverished people lived on Wall Street too?).

If you view this in terms of nation-states you will get confused (again, it’s a scale and networks thing). The United States is a major oil producer – that’s a raw material. Yet the United States is also a major producer of consumer goods – that’s core. What’s happening is that some places (and people) within the United States are peripheral to others. This is a process, a relationship, an imbalance of power. That imbalance is strongly driven by the ability to gain monopoly power. Monopolies are where you can generate massive imbalances of profit and disempowerment. One part of the process starts using another part as both a food supply and a sewer. Part of the crisis of our age is that when this hits a global scale that imbalance becomes self-destructive. You become your own sewer as you eat yourself.

Much of the world’s politics, including climate politics, is a reflection of this planetary metabolism. Globally the West has maintained its status as core relative to the rest since the colonial period (exactly who and where in the West is top of the top keeps changing. This could shift towards East Asia, hence some of our current global politics.). For climate change the core-periphery imbalance sets up an antagonism that keeps undermining the world’s ability to reach a global agreement. Some people live very high consumption lifestyles, while others do not. These two groups are kept isolated and in a state of antagonism. Why should I sacrifice my wellbeing for those people over there?

When we view the world in terms of core-periphery, we can be more nuanced than just thinking in terms of poor vs rich countries. When you look at a specific location, ask: where does this place fit in? What jobs do these people do? What part of the process do they serve? Why is it happening here and not there? Bring in both networks and scaling too, and you’ll start seeing individual unique locations as embodiments of a global world.

GLOBAL ACTORS

Fiction typically focuses on an individual main character. Most individuals do not exist at planetary scale. So, who does have the capacity to act globally?

Because of scaling, most of the time individual people are a kind of substance when viewed globally. You might vote in an election, but from a global scale it’s all just “the electorate”. Likewise with consumer demographics. Masses of people all just melt into a single substance where the individual vanishes. Those individuals might still matter – networks can amplify the effects of particular individuals (think of a virus). But at global scale this becomes so complicated and obscured with mists and fog that it’s hard to know who did what. Therefore when thinking globally we’re either looking at vast leviathans made of masses of people, or at those specific cases when one individual really does act globally (and we know who it was).

In fiction the leviathan can be explored with a representative example. The mistake would be to think the individual is taking global action as an individual. They are merely an example. In contrast, global individuals can be explored more easily at a global scale. The mistake there would be to see these people as typical experiences. They are in an unusual position of power. That power is also not to be confused for institutional authority or celebrity (again think of a virus). A president can be powerless, at global scale. An anonymous computer programmer might take actions of global significance. Institutions and visibility only loosely align with what is actually happening.

When telling a story that sits firmly at a global scale you’ll be choosing between these two types of characters. Examples or outliers. The joy of fiction is in the invention - you can trace those invisible networks in ways no scientist ever could. You can imagine the first cough that started the Covid pandemic. You can imagine the flutter of a butterflies wings, and follow it to the hurricane.

THE WEST AND THE REST

Previously we looked at the climate fight as it has occurred in the Western democracies. Four phases, starting out obscure and technocratic then escalating towards mass protest, radicalism, and social conflict. That was already such a vast story that it can feel like the whole story.

Every place on Earth has a unique part in this grand global struggle. My original plan was to do a full world tour to capture that richness. However, that would require writing an encyclopaedia. instead, here’s some of the key differences between that more simplified story of four phases, and the true breadth of global experiences.

Cultural Peculiarities

Every place has their own culture. Even if you do get a global protest wave (e.g. Friday’s for Future), when it hits the ground it will take on local flavour. These waves typically have started in the West. A recurring problem is that the tactics developed in the West often don’t work well when translated elsewhere.

For example, Japan is equivalent to any Western country economically. Their climate issues are basically the same. Culturally, Japan is very different. Western activists have relied on mass protest. Apparently Japan doesn’t do protest? Turnout is low by Western standards. Activists have to overcome more cultural inertia to disruptive change, such as the social norm of meiwaku, and the negative legacy remaining from past generation’s violent protests. The aggressive and disruptive tactics developed elsewhere don’t necessarily work the same way. Activists have to adapt.

Every place has some version of this stuff going on.

Political and Economic Peculiarities

A typical large Western country will have a particular emissions profile. So much for transport, so much for industry, and so on. The political struggle will be shaped by that economic reality.

Elsewhere those economic realities can be wildly different. That’s true even within the West. Here in New Zealand half our emissions come from ruminant agriculture. Therefore climate politics circle around the expansion of the dairy industry, the cultural heritage of sheep and beef farming, and farmers’ support for conservative politics. That’s a very different story than the oil and gas lobbying that dominates the USA.

Around the world huge variation exists. Petro-states have entire economies based on oil and gas. Some pacific islands barely have economies. Bhutan is a carbon negative country, because they have a tiny population living in a forest. Parts of the Middle East have been devastated by war. North Korea successfully reduced its emissions by collapsing into a sad puddle of stagnant totalitarianism. Every place is unique.

Authoritarianism

The West has tended to be the high point of democracy and civil liberties. Tactics of civil disobedience are much more difficult under authoritarianism. Typically authoritarians simply don’t care about environmental issues. Their main concern is to maintain power and social order (or just outright corruption). They typically try to funnel people into officially sanctioned channels. You can be an environmentalist, but only if it never threatens the social order. As a result activism often becomes smaller scale, more fragmented, and diverts energy into safer activities. Because climate activism necessarily challenges power, it risks becoming seen as a potential threat to the state, and caught up in a broader protest against authoritarian power.

For example, in China civil society is allowed to exist, but only within a box. Civil society is expected to function downstream of the state’s technocratic authoritarian environmentalism. You can have a movement, as long as it’s an officially sanctioned movement. Stuff like the China Youth Climate Action Network are the official alternative to something like Friday’s For Future (starting a real Friday’s for Future campaign will earn you a visit by the police).

I don’t think student protests are a helpful solution to the problem in China. Because of the unique cultural and political circumstances, Chinese people tend to resort to more moderate ways to voice their concerns. We need to advocate actions against climate change in ways that best suit China. For us, the best way is to work with the government and help come up with plans to tackle those issues together.

- Zheng Xiaowen, China Youth Climate Action Network executive director

As a result, in China public awareness is low. You are free to talk about climate change, but only within narrowly defined limits, in a censored media environment. None of this is likely to change while China remains an authoritarian Communist state. The aim of the state is to maintain power. Repression is aimed at eliminating troublemaking, rather environmentalism as such. Activists are unable to pressure the government, so they are safer doing grassroots community building. In contrast international NGOs and other players have the liberty to apply global pressure on the Chinese government from outside Chinese state control. States have power only at a certain scale. They can be side-stepped by mismatching that scale.

Violence

The West has also tended to be the high point for maintaining basic law and order even in the presence of serious social conflict. Elsewhere things can get much uglier. An authoritarian state might itself be using violence to suppress dissent. Violence might be pursued for resource extraction in the old colonial fashion. A weak, corrupt, or failed state may be incapable of enforcing the law. In these contexts the social conflict of a climate debate can easily be a violent conflict.

It’s also worth noting that the world’s major war zones are in regions dominated by authoritarian petro-states. That’s not a coincidence.

Petro-states

These are places where the economy is dominated by fossil fuel extraction, and the political system has merged with that industry. For example in Saudi Arabia oil profits (technically rents) are around 25% of GDP (with peaks of ~50-90%). In contrast, for the OECD countries oil profits are <1% of GDP. Petro-states do have a non-oil economy, but the oil part is so huge that it dominates everything.

This is about relative production, not total. The USA produces a lot of oil, and has a strong oil lobby, but they also have a very large non-oil economy. Oil alone can never entirely capture the political system in the USA (hence all the propaganda and alliances with religion and the far right). In contrast petro-states are dependent on fossil fuel extraction. That dependence has blown up the regular economic and political development. Hence they tend to be authoritarian, corrupt, unstable, and prone to starting wars.

Climate action is potentially an existential threat to petro-states, unless they can see a way out by diversifying their economy. Doing so would then throw them into a different kind of climate problem – development.

The Logic of Development

In the Western focused story, the fossil fuel industry was the driving force blocking action on climate change. Elsewhere that role is often taken by economic development. The dominant social issue is poverty. They are trying to climb out of the periphery and into the core.

In these places climate activism tends stay at the equivalent of the West’s Phase One. The focus is on the United Nations, NGOs, basic awareness raising, and technocratic solutions. Escalating towards mass protest is logistically much more challenging. If large scale protests do happen they are likely linked to some other related issue.

Unlike the fossil fuel industry, development could in theory be climate friendly. In practice development has involved countries building massive amounts of coal-fired generation in a race for any power at any cost. The main self-justifying narrative is the “right to develop”. Westerners often take this narrative as self-evidently true. However, this narrative leaves some big open questions. What is being developed? Why? How? For who?

We need more energy for development, our government tells us, so that the GDP (gross domestic product) stick does not ever go limp, and the poor get cheap electricity. We need new coal mines stretching for miles and more oil imports so that more big industries can come up, air-conditioned cars speed along new freeways, and huge glossy supermarkets replace shanties in clean and green new cities replacing old and dirty villages. Our per-capita carbon emission is nothing compared to that of America, or the European Union, and we have a ‘right’ to develop. You cannot deny a sovereign nation its developmental energy, and the necessary, absolutely necessary, emissions, argues the government. The mainstream media; the political, scientific, and economic fraternities; and many ‘responsible’ NGOs echo the view. Yes, there is a climate crisis. But we did not create it, and necessary adaptation and mitigation measures will be taken; a national climate action plan is on board.

Yes, but who are ‘we’? Who ‘are’ the nation we celebrate? What defines ‘development’?

- Mausam, issue 1, 2008. Newsletter of the India Climate Justice Collective

The Life of the Educated Activist in a Poor Country

The typical Western activist mostly differs from their culture in terms of lifestyle and outlook. In poorer countries this difference can be a class difference. The situation is somewhat similar to what we saw with the radical generations preceding the Russian Revolution, back when we looked at What Is To Be Done? In both cases, you have a “backwards” country which is modernizing. A small group of young people are getting Western educations, often overseas at Western universities. This leaves them somewhat stuck in the middle. They are not Westerners, but they are also in a class apart from most people in their society. In 19th Century Russia some of these people become political radicals. Today, across the world, some of these people are becoming climate activists.

This is a very different lived experience than their equivalents in the USA or Europe.

Since the very start of my environmental journey, I’ve often found myself looking up to my peers from the U.S. and Europe. I see their posts about organising rallies and protests and even filing lawsuits against their government — then I look at the work I’ve done and am struck by how small it seems in comparison. I see photos of them attending climate conferences and events together, and the friendships that have formed between them — yet Asian activists are rarely present. It’s honestly hard not to feel left out.

...

This mindset that those in the “West” are better and have all the answers, that I need to learn from them. I know from conversations with friends that I’m not alone in this feeling of inadequacy.

...

But this common thread of imposter’s syndrome amongst Asian youth activists has deeper implications.

...

A friend put it best: “Is it really because we are not doing enough compared to our western counterparts? More likely it’s just that being in the regions we are in, language differences and differing political contexts make our work less noticed on traditional platforms.”

- Kate Yeo, blog post, Imposter’s Syndrome as an Activist from Southeast Asia, 2021

WRITING A GLOBAL STORY

Okay! We have learned to think globally – connections, scale, process. We’ve considered who can act globally – vast masses or the weird complicated overflow of a connected world. We’ve learned about the climate fight in the West and around the world. How do we put this in a story? If you want to speak on climate change, at some point you’ll have to speak globally.

Let’s take a typical scene, and rethink it in terms of global thinking (connections, size, and process) to make this speak to global issues. Let’s just see how well this even works.

The Scene:

Young Jim got in a his 1985 Toyota Corolla and drove down Churchill Road - wet with rain - to his work at McDonalds. While distracted by a text message from his boss, he smashed straight into the back of Mr Singh the limo driver.

Think about this scene for a moment. This feels local, right? Hopefully you can already see how even the most simple local event includes a near infinity of global meaning.

Networks: the car is from Japan, the car is likely second hand with many previous owners, Churchill is a reference to World War Two, McDonalds and Toyota are both large international corporations, the phone uses global satellites, Mr Singh might be a recent immigrant from India, the roads are part of a road network, etc, etc, etc.

Scale: rain results from regional weather patterns, the car exhaust goes straight to the global atmosphere, the technologies of phones and cars are themselves part of the techno-sphere of the planet, etc, etc, etc.

Process: Both Jim and Mr Singh are low wage workers kept cheap to serve the needs to the limo’s passenger, the fuel and materials for everything they use was likely sourced in peripheral places, etc, etc, etc.

Any story is potentially a global story. Let’s pick just a few elements, and re-write that scene. We can’t do much with only one scene. But we can give it a more global feel.

Young Jim got in his 1985 Toyota Corolla, on old beat up second-hand Japanese import previously owned by a family in Kyoto who ran it into the ground then sold it cheap, exported overseas to be the entry for some far off teenage gaijin into the world automotive transportation. That young Gaijin Jim now turned the key and a cloud of black smoke sputtered out into the sky, mixing with the white clouds of the now fading Pacific cyclone which as yet still dominated the world from horizon to horizon. The vulcanized rubber squealed as Jim overstepped the accelerator, leaving a trail of ex-Malaysian rubber on the concrete drive.

He spun off down Churchill Road – God bless you Mr Churchill, least we now speak Japanese – and joined the flow of commuting traffic, merging into a thousand faceless automobiles following the dictates of work, money, and desire. Jim could see his own workplace ahead, the Golden Arches, that clonal American polyp that appears identical no matter if it sprouts in Mumbai or Memphis. And a lightning bolt of data struck Jim’s phone from outer-space. And the boss was annoyed that Jim wasn’t worth his wages and he better be here soon. And Jim, distracted by the message, drove the former family car of the Takagawa family straight into a limo chauffeured by a man fresh in from Mumbai.

That is one way of doing it.

You might be noticing a potential problem here. If you layer this stuff in at the level of every single sentence, you’ll start to melt reality. It gets weird. Individual human beings exist at human scale. Many of the actors at global scale simply are not individual humans.

Therefore you have some artistic choices to make. Here’s some ideas:

Embrace the weirdness (see Being Fantastically Wrong, The Weird, and Modern Epic). Follow all the connections like I just did above.

Ignore the global. This is the easy option. Tell a regular story the regular way. That’s still a valid story. The downside? You have missed an essential aspect of climate reality. It is global. You’ll be relying on the reader to fill that gap.

Get global with examples or outliers. You might need a few characters, placed in different locations, scales, or positions in the web of connections. Again, this starts pushing you towards Modern Epic.

I suspect those are your three big options. Maybe you can come up with something else?

CONCLUSION

The world is a big place. I know I’m leaving an encyclopedia’s worth of stuff out. Hopefully that is enough to stimulate your own thinking. Climate change is global. You need to think globally. With a bit of creativity you can tell a global story.

Return to menu.